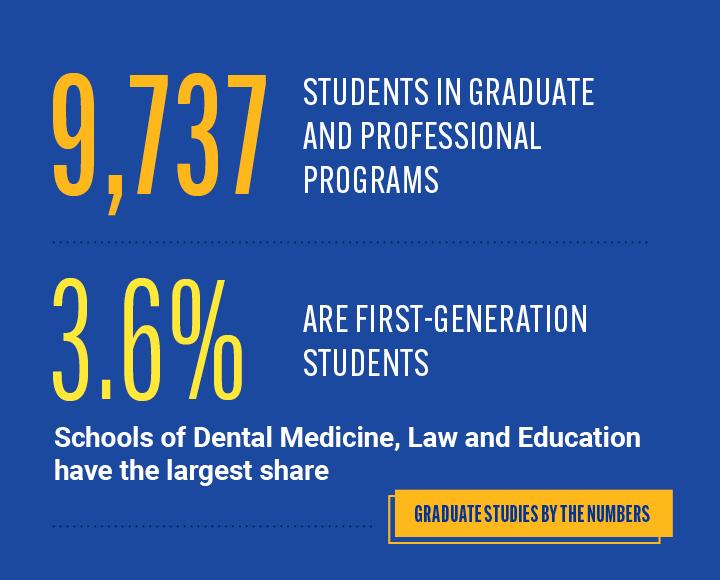

Back in the fall of 2023, Luana Reis, Gabriel F. Quinteros, Melanie Blassingame and Paul McMahon all find themselves in the swirl of the 9,268 students who are pursuing graduate and professional studies at the University of Pittsburgh. They’re shaking hands with new people, opening their minds to new ideas.

In many ways, they represent an emerging trend. They are unconventional graduate students: They are older than 25, come from established careers, have families, are from outside of the United States are first-generation college students, and are using graduate studies to ignite or reignite their intellectual passions.

“Unconventional is becoming the norm,” says Amanda Godley, Pitt’s vice provost of graduate studies. “We see students choosing to come to graduate school at all points in their life and for all different reasons. The old model of going right from undergraduate is changing at Pitt and across the United States.”

The years before Pitt

Luana Reis

It is noontime, and the young girl makes her way through the warm, busy streets of Feira de Santana, in Bahia, one of Brazil’s most populous states. Luana Reis is on her way home from lower school, and she’s brought her lessons with her. She sits with her single mother in their modest home, sharing with her much of the same instructions she’s just received from her teachers.

Education and literacy had escaped generations of women in Reis’ family. They were the women who worked the land — farming, planting, and taking care of animals — and who cleaned other people’s houses. When Reis was born, her mother, Analice, told her things would be different. “Your responsibility,” she directed her daughter, “is to study.” She wanted her to dream.

As the two learned together, her mother reinforced the value of a formal education as a way forward in society. But the daughter also absorbed lessons beyond the school walls that would deeply influence her life as well.

As they sat, Reis listened to her mom’s poetry and songs. In them, she heard the lullabies of all the African-descended women who came before her. They were women who were not able to read or write, yet they contributed to the quilombos — free communities built by escaped Africans — that were scattered across 17th-century Brazil.

These women, lost in the formal education system, were found by Reis in her mother’s stories. And one day, somehow, whatever it took, she was going to tell them.

Gabriel F. Quinteros

In the panhandle of northwest Texas, Gabriel F. Quinteros’ potential seems as wide open as the cottonfields surrounding his hometown of Lubbock. He fills his days playing the cello, singing in the choir and swimming. Influenced by listening to National Public Radio, he dreams of traveling, using his bilingual skills to bring stories to the world.

At 18, in 2008, he went off to Texas Tech to pursue a dream career in journalism. But something nagged at Quinteros. As a member of the LGBTQ community, he felt boxed in by a bigotry that he felt swept across most of the flatlands. His earlier experimentation with drugs and alcohol left him feeling free of the stigma and inhibition of being what he called “different.” The experimentation became addiction. In the midst of his struggles, he left college. But thanks to broad support from his family, the community and professionals, he was able to re-center himself. He went back to school in 2014, finishing three years later at age 25 with a degree in Spanish and a minor in addiction studies. Along the way, he always had one question: Where were the therapists to aid his recovery who looked like him, who identified as he did? To change this circumstance for others, Quinteros would need to uproot himself and imagine a new way forward.

Jump to Quinteros' time at Pitt.

Melanie Blassingame

Of all the seasons, Melanie Blassingame most looks forward to summer. Growing up in Keisterville, what she calls a small “patchtown” outside of Uniontown, Pennsylvania, she spent the warm weather months working in amusement parks. She calls it the most “fun job” ever, and she pours her heart into helping people enjoy themselves — as if they were on vacation, an experience her family could never afford.

Blassingame persisted through the financial struggles and her father’s death and became the first in her family to attend college. She started at West Liberty University, majoring in psychology. But after an internship with Disney and the joy she found in amusement parks, she felt her next steps should be in marketing and entertainment, making a living bringing people smiles. In the fall of 2013, she transferred to Pitt, where she took some marketing classes and had a chance to study in Italy. When she graduated in December 2015, despite her emerging interest in marketing, she finished with a degree in psychology. As she pursued a related career, she found a position helping adults with severe and persistent mental illness lead stable, active lives. This was her first employment in this field and starting in an area where so much was unknown to her was “scary” work. But the work touched her in ways she could not imagine. Over the next five years, she discovered a renewed sense of how to help people find their “smiles.” Now, all she has to do is move toward her new passion.

Jump to Blassingame's time at Pitt.

Paul McMahon

In high school, in Erie, Pennsylvania, Paul McMahon plays baseball and wins wrestling matches. He is athletic and works hard, but when he goes off to Edinboro University — one of the first in his family to attend college — he commits himself to something larger. He studies physics and joins the Army ROTC. Science and service to others are the twin pillars that propel his all-American journey.

When he graduates, he becomes a leader in a specialized military group called Explosive Ordinance Disposal.

Twice deployed to Afghanistan, he neutralized IEDs, manually retrieved bomb detritus to ensure troops and civilians are safe and supervised analyses of bomb evidence to inform mission decisions. He earned two Bronze Stars. When his deployment is over, his career shifted from high risk to high reward. The soldier became a teacher. He earned a master’s in education at Slippery Rock University, and he concentrated in STEM, giving instructions on robotics and engineering alongside lessons in discipline and responsibility to his students in rural Pennsylvania. After about a decade in the classroom, he yearned to reinvent himself. He turned his face to the future; a new dream is brewing.

Graduate school at Pitt

Pitt places graduate programs into four categories: research doctorates (such as PhDs) and professional doctorates (such as MDs or a doctorate of physical therapy or education); and research master’s degrees (typically MA and MS degrees) and professional master's degrees (such as the Master of Social Work).

Some graduate offerings are online or are hybrid, which are typically for professional programs, not for research-oriented master’s and doctoral work. The only campus other than Pittsburgh to have a graduate program is Bradford, which offers a master’s degree in social work.

In addition, there is graduate programming that doesn’t confer a degree but grants a credential or certificate for expertise in a certain area.

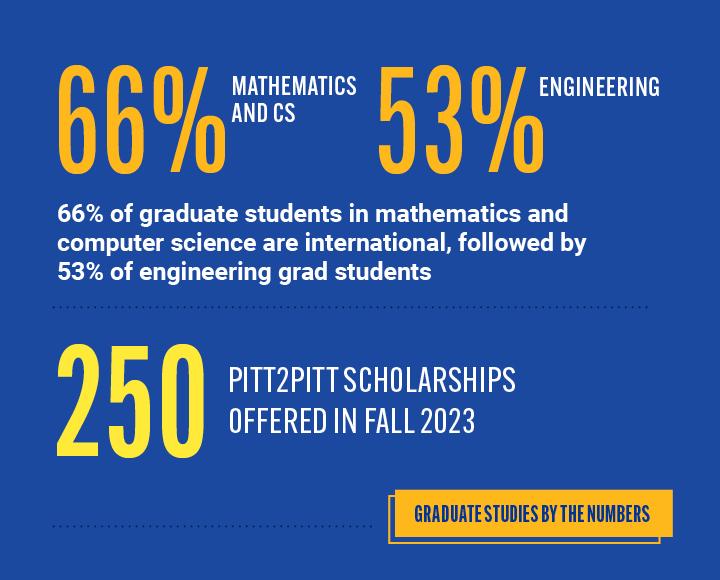

At Pitt, graduate programs in business, law, engineering and public health rank among the top 50 programs in the world, according to data from U.S. News & World Report. Also, for the past decade, says Godley, about 22% of Pitt’s graduate and professional students have been international students, enhancing Pitt’s role as a world-class research university, one that is able to connect diverse graduate students with professors doing cutting-edge work.

Once on campus, Godley says, graduate students find diverse opportunities for support and engagement. A new staff member in graduate studies supports engagement and belonging. The 30-year-old K. Leroy Irvis Fellowship has been revamped to include national networking with a project sponsored by the Southern Regional Education Board. There is a partnership that supports a peer mentoring program for international students called Graduate Global Ties, and a graduate fellowship advisor is onboard to help graduate students search for and apply for national and international fellowships.

“Graduate Studies is building critical partnerships across the University,” Godley says, “and thinking more broadly about how to support graduate students.”

The decision to come to Pitt

Luana Reis, Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, 2025

Pittsburgh, summer 2017, a colleague’s suggestion launches a new journey

Reis first arrived at Pitt in 2013. She was fresh from Brazil, where she had earned a master’s degree and was then awarded a scholarship through the Fulbright Foreign Student Program that enabled her to teach Portuguese in Pitt’s Department of Spanish and Portuguese.

After nearly a year of teaching, in 2014, she returned to her home country. But after two years there, she came back to Pitt thanks to Brazil’s Leitorado Fellowship, which places Brazilian lecturers in universities around the world to raise awareness about the country’s literature, culture as well as the linguistic diversity of Brazilian Portuguese.

As Reis was about to complete the fellowship, the coordinator of Pitt’s Portuguese program encouraged the young lecturer to pursue a PhD at Pitt. Reis was excited to apply but had to defer a year to complete her lecturer responsibilities. In the fall of 2018, she began graduate school at Pitt, where with her deep interest in language, she’s using poetry to explore women’s contributions to the quilombos.

Reis never forgot her mother’s stories. “It’s important to consider,” she says, “that the quilombos were not just spaces in opposition to colonialism, but spaces where people were able to create new meanings for themselves — peace, healing, language, family — and women were a part of this creation.”

The University’s broad library collections enabled Reis’ research, helping her to find and document the stories she heard so long ago at her mother’s table. “The library has an amazing collection of Latin American books.” Reis says. “I can find books for research here that I couldn’t find in Brazil. It all seems so magical.”

Along the way, Reis has received three fellowships that have supported her dissertation, which is non-traditional as much of it is being written in poetic form.

In 2021, she earned the Andrew W. Mellon Predoctoral Fellowship; in 2022, the Immersive Dissertation Research Fellowship, supported by the Andrew W. Mellon-funded Humanities Engage project; and in 2023, the Provost’s Dissertation Completion Fellowship for Historically Underrepresented Doctoral Students.

A Humanities Engage Summer Administrative Micro-Internship supported Reis during a season when her international status didn’t allow her employment outside of the university system. She worked with the Office for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion on the initiative “Black Lives in Focus,” a multimedia project.

In the classroom, Reis and her students also created the group AddVerse. They began by exploring Brazilian poetry but would soon “add verse” from different Latino cultures that explores resistance and social justice and notes how participants can use words to battle oppression. AddVerse was recognized for its commitment to equality and justice at the University’s 2024 K. Leroy Irvis Black History Month Celebration.

Reis is completing her Pitt dissertation at Princeton, where she accepted a position in fall 2024 to teach Portuguese.

Gabriel F. Quinteros, schools of social work and public health, 2025

Dallas, spring 2022, a chat with a Pitt alum defines a new direction

Once he finished at Texas Tech, Quinteros moved to Dallas and worked for seven years in nonprofit and corporate America. He aided unaccompanied minors from Central America, helping them reunite with families and navigate the education and legal systems in their new country. He also worked with Medicare providing outreach to clients.

But he felt creatively limited at work and was deeply bothered to see how existing systems seemed to diminish people’s dignity. To break into something new, in early 2022, he decided to look into graduate schools. That’s when Pitt alum and former social work professor Margaret Elbow suggested he consider Pitt’s joint social work and public health master’s degree. The program fit his desire to provide both mental health care and clinical counseling. He applied. By August 2022, he was in Pittsburgh, partially attracted by the city’s green spaces. Once classes began, Quinteros was impressed by his experience. He felt drawn to his adjunct professors and their experiences in the “real world”; he valued the work at the Center for Race and Social Problems, and he was over the moon to have his first-ever class with an Afro-Latino faculty member, Assistant Professor Victor Figuereo, which “was really cool,” he says.

A wealth of other experiences bolstered his graduate experience, too. He draws from his long-term recovery to serve as a peer specialist at UPMC for others with similar addiction experiences. He earned an Albert Schweitzer Fellowship, which supports his work with youth and mental health at Casa San Jose, a nonprofit center serving the Latinx community.

He says Pitt is enabling his dream of being a change-maker. “I want to be a part of the community that helps. I don’t want to demand representation, but I want to join the ranks. Pitt is helping me to be the person I needed so much when I was younger.”

Melanie Blassingame, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, 2026

Uniontown, winter 2022, a dinner with friends changes everything

In the nine years since earning her undergraduate degree, much has changed for Blassingame. She’s had positions in group homes, she’s cared for individuals, she’s worked at health care institutions. She fell in love with the people and the work and she “wanted to do more.” About three years ago, at a small gathering with friends, all of whom had graduate degrees, that “more” became apparent. She determined she, too, would go to graduate school.

A web search for career options led her to Pitt’s School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. She enrolled in 2023, seeking a doctorate in occupational therapy. Her “fun” work had now become fulfilling.

“Being able to help someone budget their Social Security income, help them find work, pay their rent, live independently is important,” she says. All of it fits the textbook role of occupational therapy — using everyday life activities to promote health, well-being and fuller living. “But,” Blassingame adds, “most awesome is helping them to live against the odds of what others may think they can or cannot do. That is what brings me the greatest joy.”

Recently, Pitt’s occupational therapy program was rated No. 1 in the nation by U.S News & World Report. The program gets high praise from Blassingame, who appreciates how her lived and work experiences resonate in the classroom.

She says the fieldwork and capstone requirements, which put students in direct contact with professionals and practice, have benefits for the clients she’s aiding. At the moment, she’s a live-in provider at a small group home on Pittsburgh’s South Side. “What I’ve learned in the classroom has been valuable as it translates to the work I do in real time,” she says.

In addition, the knowledge-building and reliance on evidence-based research to guide the learning is the “most thoughtful,” she’s seen: “We’re always learning, and it feels like the intention is bigger than just taking an exam.”

Paul McMahon, Katz Graduate School of Business, 2024

Basye, Virginia, spring 2020, a mountain-bike race creates a fresh path

About four years ago, McMahon was sweating and running through the Virginia woods on an endurance race. As a teacher, his robotics classes gave his students permission to imagine. It was no different for him. So, as he sped through the forest, he passed ideas back and forth with a friend on what they’d like to invent. They settled on creating a cold brew coffee.

McMahon’s start-up, Kevo Brew, introduced him to all sorts of business processes — prototyping, networking, marketing — and he was hooked. He decided to go to business school. He went online, searching for business degrees and up pops Pitt’s MBA. Two months later, he was in class at Katz Graduate School of Business, which was ranked among the top 25 best public business schools in the nation in 2023 according to Bloomberg Businessweek.

McMahon is 38. “On paper,” he says, “I felt just a little of out of place because I skew to the older side of things. But in the overall experience, I feel accepted, and everybody treats me as if I belong. I have a friend in the program who’s 58, and I look toward him for inspiration.”

McMahon used his GI benefits and entered into a program where he felt supercharged by classes in accounting, economics and product development. A favorite was the Katz Global Research Practicum, a three-credit course with a study abroad component in Chile. There they studied different agricultural startups, focusing on how the businesses were adapting to drought and water shortages. The travel and the class connected him more deeply to the importance of sustainability and, while he didn’t speak Spanish before he went, the class inspired him to take language lessons.

After teaching his students through the COVID-19 pandemic, the in-person business classes were another draw for McMahon. He makes the 90-minute drive to the urban campus from his home in Mercer County to brainstorm and collaborate in the same room as his colleagues. He’s found the professors accessible, the recitations supplemental to learning, and seminars with business executives all incredible opportunities to grow.

McMahon finished the program a few months ago. Today, he’s a project coordinator with Westinghouse headquarters in Cranberry, working to help innovate the energy supply with a zero-carbon emission footprint.

Interested in graduate school at Pitt? Alumni receive up to $7,500 in scholarships annually with the Pitt2Pitt program when they enroll in a participating Pitt graduate or professional program.